Over at Letters Blogatory, Ted Folkman has picked up the decision of the Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) on judicial assistance on which I reported earlier this week. Ted found a nice name for the case, In re Frau R.*, and shared an interesting observation from a US perspective:

Over at Letters Blogatory, Ted Folkman has picked up the decision of the Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) on judicial assistance on which I reported earlier this week. Ted found a nice name for the case, In re Frau R.*, and shared an interesting observation from a US perspective:

“I have little to add about the case itself, though I think it is an excellent illustration of the civilian way of looking at things. In Germany it is the court’s obligation to obtain the relevant evidence, and so when the court fails to do so, the litigant is deprived of her constitutional right to the protection of the courts, because it is the court that has failed. Things are different in the common law world, where in general the burden of obtaining the relevant evidence falls on the party. In his post, Peter points out that the court’s burden to obtain evidence is especially heavy in family law cases and perhaps less heavy in civil or commercial cases, but he nevertheless expects that the same outcome could obtain in cases where, for example, the court fails to make a request under the Hague Evidence Convention on the motion of a party. That is an almost inconceivable result, at least in constitutional terms, in the United States, where we do not think there is a constitutional right to pretrial discovery. So there is no small irony in this result.”

When I first read Ted’s comment, I took issue with the statement that in “Germany, it is the court’s obligation to obtain the relevant evidence”, as it struck me too far-reaching: German procedural law places the burden of offering the evidence on the parties. The duty to establish facts ex officio is an exemption; the most relevant application being in family law matters. On the other hand, the parties can only “offer” evidence, as the German technical term Beweisangebot nicely illustrates. It is for the judges to accept that offer: They control whether witnesses or experts that have been offered will actually be heard, and if so, which ones. Parties are free to introduce documents that they have in their possession into the proceedings, but access to documents they do not have in their possession again is controlled by the Courts, and so is the decision whether to seek judicial assistance, be it with respect to witnesses or documents abroad. So with that in mind, Ted may have overstated things only slightly.

* For some of the more bizarre examples of anonymous case reporting in Germany, see my earlier posts here and here.

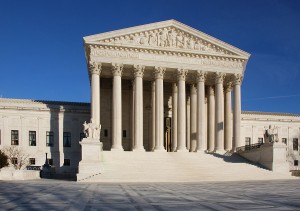

The photo shows the US Supreme Court. Copyright Attribution: Jarek Tuszynski / CC-BY-SA-3.0 & GDFL via Wikipedia.

Peter, I accept your charitable amendment to my statement about German law!