In a judgment handed down on March 16, 2012, the Federal Supreme Court (Bundesgerichtshof) ordered the German Historcial Museum (Deutsches Historisches Museum) in Berlin to return the art collection of Jewish art collector Hans Sachs to his son. The Federal Supreme Court reversed an earlier decision of the Berlin Court of Appeals (Kammergericht). This brings a long-running litigation to an end.

In a judgment handed down on March 16, 2012, the Federal Supreme Court (Bundesgerichtshof) ordered the German Historcial Museum (Deutsches Historisches Museum) in Berlin to return the art collection of Jewish art collector Hans Sachs to his son. The Federal Supreme Court reversed an earlier decision of the Berlin Court of Appeals (Kammergericht). This brings a long-running litigation to an end.Dr. Hans Sachs was born in Breslau in 1881 and died in New York in 1974. He was a Berlin dentist and had built a unique collection of some 12,500 posters, which documented the beginnings of the modern advertisement industry. Having been arrested on November 9, 1938 and deported to Sachsenhausen, Hans Sachs and his family were forced to emigrate to the United States some weeks later. His collection had already been seized earlier in the year by Goebbels’ Reichspropagandaministerium. It was intended to become the foundation of a National Archive of Propaganda.

After the war, the collection could not be located. It was not until the 1960ies that parts of the collection reappeared in East Germany. Hans Sachs learned about this, but during his lifetime did not take any steps to reclaim the collection. Nor did his heirs, until 2006, when Hans Sachs’ son asserted ownership of the collection and subsequently took legal action against the museum.

The Federal Supreme Court was faced, on the one hand, with a variety of factual questions which could not be answered with certainty, such as the precise date and context of the seizure in 1938, and the alleged sale of the collection to an acquaintance of Hans Sachs prior to his emigration. On the other hand, there were three major legal issues to be decided:

First, had Hans Sachs lost title to the collection. If not, the second issue was whether his heir as owner was barred from reclaiming the collection, since the restitution legislation took priority as lex specialis. Finally, the museum had relied on the doctrine of estoppel (Verwirkung) since the Sachs family had taken no action between reunification and 2006.

On the first legal issue, the Federal Supreme Court held, as had the first and second instance, that Hans Sachs never lost title to the collection. It then held that while the restitution legislation is generally the exclusive remedy, this would not apply when the assets in question were considered lost when the restitution remedies became time-barred. Finally, the Court held that the lack of action over a 16 year period was not suffient for the claim to have become estopped.

Of course, the findings on estoppel are highly case-specific and can not easily be generealized. The finding that the ownership claim can, in specific circumstances, take prioity over the restitution remedies, however, appears to have implications for a wider class of cases of lost art. It is this finding which is creating a new, and somewhat surprising precedent.

As other commentators have pointed out, the Berlin Court of Appeals (Kammergericht) was in line with the previously prevailing interpretation of the law. On that basis, the Berlin Court of Appeals had in its judgment not granted leave of appeal (Zulassung der Revision).

The German Historical Museum has published, on its website, a chronology of the Hans Sachs Collection and its historical context, as well as a short biography of Hans Sachs. Not surprisingly, given the litigation background, the chronology appears to be somewhat biased, but still sets out the history of the collection and its political context.

The German Historical Museum has published, on its website, a chronology of the Hans Sachs Collection and its historical context, as well as a short biography of Hans Sachs. Not surprisingly, given the litigation background, the chronology appears to be somewhat biased, but still sets out the history of the collection and its political context.

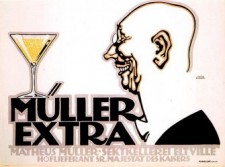

The illustrations above show the cover of “Kunst! Kommerz! Visionen! – Deutsche Plakate 1888-1933″, the catalogue of the 1992 exhibition in Berlin, edited by Deutsches Historsiches Museum, and Julius Klinger’s 1912 poster “Müller Extra – Suppliers to His Majesty the Emperor”, both (c) Deutsches Historisches Museum.

[…] Bundesgerichtshof judgment in the Sachs Art Collection Case (see March 19, 2012 post) is now available online in full. The court based its ruling on the concept that restitution in […]

Sehr gehrte Damen und Herren, ich beschäftige mich ehrenamtlich intensiv mit der Fage der Verjährung bezg. der Rückforderungsansprüchen vonRaubkunst. Können Sie mir das Aktenzeichen des BGH mitteilen betr. Das Sachsurteil?

M ihr Danik für Ihre Bemühungen. Klaus Dittmann Rechtsanwalt

Sehr geehrter Herr Kollege Dittmann, das Urteil des BGH vom 16. März 2012 hat das Az. V ZR 279/10. Mit freundlichen kollegialen Grüßen, PB

[…] In the 2012 landmark Hans Sachs case, for example, this defense was not invoked by the Deutsche Historisches Museum, and hence, when the […]